- Reviews

- Best Classic Cars

- Ask HJ

- How Many Survived

- Classic Cars For Sale

- Insurance

- Profile

- Log out

- Log in

- New account

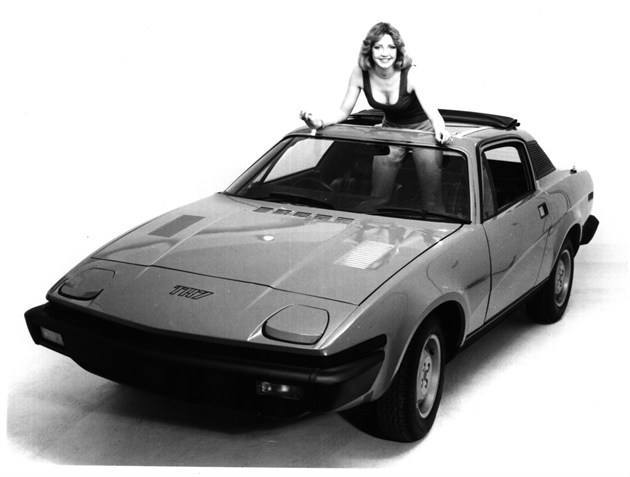

Triumph TR7 and TR8 (1975 – 1981) Review

Triumph TR7 and TR8 (1975 – 1981) At A Glance

When Triumph launched the TR7 in 1975 (in the USA; the UK had to wait until 1976), it was a clear signal that the company was making a big change in terms of the direction of the long-lived TR line. And even today, some people will find the wedged-shaped sports car a disappointment after the rorty, six-cylinder TR6. In short, TR7 was the encapsulation of British Leyland's corporate design direction, and it meant the car gained a roof and lost two cylinders, 500cc and independent rear suspension.

And It really wasn’t a true TR, as there wasn't a convertible option at all from launch. Triumph had been forced into taking the decision about it as a tin-top on the back of threatened US legislation banning open-topped cars. In the end, that never happened and the convertible TR7 arrived in 1979. But for all the criticism over these points and the wedge styling, it sold faster than the TR6 ever had. It’s a much easier car to live with too, driving more like a two-seater saloon than a sports car. It’s also by far the cheapest way to join the ranks of Triumph TR ownership.

In 1980, the V8 powered TR8 was launched. This was the car the TR7 should have been – after all, it was designed to accept the Rover V8 engine from a very early stage in the project. Sadly it arrived too late, was in production for less than two years and nearly all were left-hand drive examples sold in the USA. A handful of UK cars escaped into the wild – many more have since been created on a DIY basis - some cars clearly have been converted more professionally than others. Brilliant to drive, good fun, and surprisingly effortless to drive.

Ask Honest John

Is the Triumph TR7 car a good investment?

Model History

- January 1970: Following the cancellation of separate MG and Triumph projects, BL executives instigate plans for a new corporate sports car

- January 1972: TR7 styling starts to take shape

- May 1973: Lynx project comes into focus

- September 1974: Production starts at Speke

- January 1975: Triumph TR7 launched in the USA

- May 1976: TR7 launched in the UK

- October 1976: Speke workers go on strike, ultimately leads to the factory closing and the cancellation of Lynx

- May 1978: Production moves to Canley

- May 1979: Convertible version launched

- March 1980: Triumph TR7 convertible launched in the UK

- May 1980: Production transferred to Solihull

- October 1981: Production ended

January 1970

Following the cancellation of separate MG and Triumph projects, BL executives instigate plans for a new corporate sports car

Sports cars were something that both BMC and Leyland as separate companies had proved to be rather good at. In the USA, the MG Midget and MGB had enjoyed immense popularity, outselling their rivals, the Triumph Spitfire and TR6 by a considerable margin, but when BMH were taken over by Leyland to form BLMC, new dilemmas began to rear their heads. It was fairly obvious that the MGB and TR6 were reaching the end of their useful lives; despite healthy sales in the USA and that being the case, the question of how to replace them would need to be answered before development of any new sports cars could commence.

The root of this dilemma was that although MG and Triumph belonged to the same company following the merger of 1968, up to that point, they were rivals and subsequently, there was considerable overlap in BLMC’s sports car range. The MG Midget and Triumph Spitfire were aimed at the same customers and the Triumph TR6, GT6 and MGB were not too far apart, either. The result was that there were five models competing in pretty much the same sector – and all selling in comparatively small numbers in comparison with the other sub-two litre cars being produced by BLMC at the time.

At the time of the merger, both MG at Abingdon and Triumph at Canley were already working on their own interpretations of how their new sports cars would appear and be engineered – and the contrast between both companies would prove to be highly interesting.

In Abingdon, MG had been working on a promising sports car, codenamed the ADO21, which was a shark-nosed two-seater sports car, which unusually for its time, sported a mid-engined configuration. Of the other interesting technical aspects of this car, was the fact that the only major carry-overs from the BMH saloon car range was its engine and Hydrolastic suspension; it has been said by MG enthusiasts that this car was essentially an MGF, some twenty five years ahead of its time.

MG's option was the rakish ADO21. Sadly, its mid-engined configuration and hydrolastic suspension ruled it out of the running for the corporate sports car... BL wanted plain and simple for its US export.

Over at Triumph, initial work had also started on their own sports car, codenamed, ‘Bullet’ and unlike the MG ADO21; this was a conventional front-engined car, using saloon car running gear. The cars may have conceptually been diametrically opposed, but elements of both cars would end up being incorporated in the final product.

The Triumph Bullet offered everything that the Americans told the British what they wanted from their sports cars: it was simple mechanically (front engined, rear wheel drive), which gave a greater potential for long term reliability. As far as BL was concerned, that made it a preferable option to the ADO21 for the company's corporate sports car.

BLMC management knew that they had to carefully pitch any new sports cars at an increasingly sophisticated clientele – and the cars they were currently selling were, to put it politely, getting over the hill. In the USA, the company’s biggest export market, buyers were turning to the offerings Datsun (the 240Z) and Porsche (the VW-Porsche 914) in increasingly large numbers and so, whatever BLMC would serve up would need to be quick and reliable (to match the Datsun) and technically interesting (to match the mid-engined Porsche). Also new crash legislation was being introduced in the USA, which many informed people in the motor industry assumed would prove to be the death-knell of open topped sports cars. Because of these pressures on BLMC and the fact that there was a massive need to develop a viable range of family cars, money and resources would only be released to develop one ‘corporate’ sports car.

Of course, the marketing issue would need to be finalised first and because of this, in late 1970, Mike Carver, then a manager in Central Product Planning and Spen King travelled to the USA in order to sound out the dealers and try and understand what it was that would be required. The fact that Spen King (at the time, the Chief Engineer at Triumph) would be so intimately involved in the early stages of the new car’s development ensured that Triumph as a marque would get the inside track in terms of development. This would be in spite of the fact that of the Corporation’s sports cars, it was the offerings from MG that were most in demand. Carver stated subsequently, that this was in no way intended to be a full market research programme, but a series of, ‘extended conversations with relevant parties.’

The result of these findings would prove surprising because they indicated that what the Americans really wanted was a conventionally-engineered front engine, rear wheel drive car. The reasoning behind this was that the Americans wanted reliability and the ability for a ‘quick fix’ should the car fail. Once back in the UK, the Product Planners reasoned that this format also had advantages in terms of development – and the fact that it would be less costly for the company both in terms of time and finances. Donald Stokes wanted the company to have a product ready to sell by the mid-’70s and this tight deadline would be easier to meet if the product the company was developing a car that shared componentry with mass-produced stable mates.

Because the dealers wanted a car that occupied a similar place in the market to that of the biggest seller, the MGB, the advantages of the mid-engined layout were lessened significantly. Performance would not be great enough to exploit the handling advantages brought about by even weight distribution that comes with a mid-mounted engine and because the new car would be a two-seater, there was no advantage to be found in either configuration. In the end, it would come down budget: front engine, rear wheel drive it would be.

Out of the MG and Triumph models in development, it was obvious that the Triumph Bullet would be the model to be honed into a production reality. Work on the Bullet had been ongoing since 1969; Triumph envisaging it as a combined GT6/TR6 replacement and prototypes were soon running with Triumph four and six-cylinder power units. Once the green light had been given to the Bullet project by the BL Board, the full weight of the company’s (limited) resources were put behind the development of the new Triumph at the beginning of 1971.

Donald Stokes made it clear that it should be ready for introduction in 1975. The Bullet was being developed as a cheaper front-engined version of the VW-Porsche 914 and as such, was not a full convertible, but a targa-top, rather like the Fiat X1/9 – this left a gap in the range for a full convertible and the MGB would be left to remain in production for as long as regulations allowed the company to sell rag-tops. Product planning decided that even though the new car was conceived as a straight replacement for the MGB, it should be priced above the older car so there was no clash between old and new. Already, the Bullet was being moved away from its intended market, by the product planners… something that would happen again and again in the Corporation.

The conception of the car was finalised; the finer details needed to be decided. Spen King was placed in charge of the development of the new car – and in a theme common with the subsequent Rover SD1 and Austin Maestro; the package would offer no technical surprises. The engine would be a development of the slant-four Dolomite engine, initially coming with a four-speed gearbox (developed from the Morris Marina) and live rear axle. Now that the ethos was for the production of a BLMC sports car (as opposed to a Triumph sports car), the option of a Triumph straight-six powered version was dropped in favour of the use of the Rover V8 engine, which at the time, was being used in the Rover P6B, P5B and Range Rover. King was an expert of honing conventional components into something comparable with more exotic rivals – and even though the rear suspension was not independent, with careful development and thoughtful axle location, it proved possible to make the car ride and handle at least as well as its foreign rivals – and certainly better than the aged MGB and TR6.

At this point in time, it became obvious to everyone that the Bullet should be marketed as a Triumph; MG still had their MGB to sell, but the Triumph range would be cut at the expense of the GT6 and TR6. Obviously, with the predominantly ex-Triumph bias in the company’s management, this decision would have not met too much in the way of debate, but following MG’s fall from favour within the company following the merger this decision surely must be seen as illogical in retrospect. During the early stages of development at Longbridge, there were TR7 shaped clay models produced wearing the ‘MG Magna’ nameplate, but it was a half-hearted effort, really. The name of MG was synonymous with open topped sports cars in the USA, and this meant that while the MGB remained in production, it would not make sense to develop an MG-badged TR7.

January 1972

TR7 styling starts to take shape

Early Harris Mann styling sketch shows that the TR7’s essential character made it through to production, although the final result was somewhat watered-down from this bold proposal.

Now it was settled that the new Triumph TR7 would not directly replace the MGB, but would also fight competitors higher up the price scale, its simplicity could prove to be a hurdle to sales. Even with the extra equipment added to the car in order to become a price replacement for the TR6 or GT6, the mechanical layout as chosen by Spen King did lead to the impression that the car was giving something away in terms of sophistication to its foreign rivals. With this in mind, the Longbridge studios were asked to re-style the car, in order to increase its appeal; and following his work on Project Condor, Harris Mann was handed the task…

1971 and the Triumph TR7 styling is almost finalised. Impact absorbing bumpers are incorporated and compared with the styling of the earlier Bullet proposal, looks good while managing to integrate the monolithic US-style bumpers, and this model does without the targa roof of the earlier car. This particular clay model sports the "MG Magna" badge, but in reality, thanks to the way the sports car plan shook out, the MG TR7 was never much more than a pipedream - at this stage.

Harris Mann honed the styling in order to give the TR7 a more expensive look – also incorporating the 5mph impact absorbing bumpers that the car would require in order to meet upcoming US regulations. The most startling aspect of the styling though, was reserved for the belt-line, which to emphasize the low nose/high tail stance of the TR7 was slashed down the side of the car starting high at the rear end-and and tapering towards the front, ending just before the front wheel. It certainly gave the TR7 a degree of character and identity that the Bullet lacked. Elements of the ADO21 design were also included, especially around the area of its pointed nose and pop-up headlights. It was at this point in time that the targa top arrangement of the Bullet was dropped because the spectre of a complete ban on convertibles in the USA was still hanging over the car industry and it still was not known whether this arrangement would meet such regulations. Happily for the management (but perhaps less so for the dealers), the Triumph TR7 would feature a ‘family’ look shared with its Austin-Morris stable mates, dropping all stylistic links with Triumphs of the past.

As development progressed, by 1972, it became clear that the TR7 should be the starting point for a modest range of sports cars – and the TR7 in the form it was launched would be the base model in this range. Because it was obvious that the torquey Rover V8 engine would suit the car perfectly, this would head the range, but below that, the 16-Valve version of the slant-four Dolomite engine, at the time under development by Spen King and being readied for the Dolomite Sprint was also earmarked to form the basis of the TR7 Sprint. Beyond this extending of the range of engines, at the point that the TR7 was nearing announcement, development of a 2+2 version commenced, with a view to widening the appeal of the corporate sports car. The thinking behind this car, called the Triumph Lynx was that with its extended accommodation, it could be an effective competitor to the Ford Capri; a car which was proving to be a runaway hit for Ford and in the process, was re-inventing the sports car market in the UK and Europe. The V8 engined Triumph Lynx would be pressed into service as a replacement for the troubled Triumph Stag, which at the time, was costing the company a packet in warranty costs.

May 1973

Lynx project comes into focus

Where certain critical people in the past have said that the Leyland Princess resembled a car styled by two different people who were not on talking terms – one for the front and one for the back, the Lynx actually was! The styling might have been an unhappy mix of Harris Mann front and Canley studios rear, the concept was impressively on target. The V8 engined hatchback Lynx would have comfortably beaten the V6 Ford Capri at its own game.

The Triumph Lynx would form the basis of another sad BL story – a victim of lack of funds, but more accurately a victim of the ongoing battle between Michael Edwardes and the unions.

The ideology behind the Lynx was straightforward enough – and the fact that strategists identified the need for the company to produce to a sports coupé proved that they were doing their job correctly. In 1972, the Lynx emerged as a wholly predictable extension of the TR7 platform, relying on its front end almost unmodified, but from the scuttle line back, the car was almost entirely new. The TR7 platform had its wheelbase extended by a full twelve inches and longer passenger doors were incorporated in order to balance the side view of the car and improve access to the rear seats. The rear end of the car looked vastly different to the donor car and was somewhat unhappy in its detailing – losing the Harris Mann tapering belt line in the process. The intention was that the car would also incorporate a hatchback, like the MGB GT in order to offer a practical, as well as stylish package.

The Lynx was a production ready reality and in this form, was scheduled to go into production by mid- 1978. When Michael Edwardes closed the Speke factory in the spring of 1978, the Lynx died with it.

Development of the Lynx was stepped up, following commencement of TR7 production in September 1974 and again, extensive use of the BL part bin was made. The gearbox would be the 77mm five-speed unit planned for the TR7 V8 rally car and Rover SD1; the rear suspension would also be shared with the Rover SD1 – a solid rear axle with intelligent location and damping. The package looked very viable and once it became clear that Speke would have the excess capacity to produce it, the BL Board gave it the go ahead for production.

September 1974

Production starts at Speke

The problem was that the time that the tooling was ready to be installed into the Speke factory coincided with industrial relations problems of biblical proportions between the workforce of the Liverpool factory and the company’s management. The turning point for Speke came with the installation of Michael Edwardes at the helm of the company – a man whose task it was to break the Union stranglehold on the company’s factories. At the end of a particularly bitter four-month Strike at Speke, the factory was axed – and with it, the Lynx.

January 1975

Triumph TR7 launched in the USA

TR7 as it appeared at launch time in the UK... styling was best described as controversial, and one aspect that grated with many enthusiasts was the ride height. This was a side effect of Spen King's practice of giving his car long suspension travel.

Speke was the factory chosen to build the TR7 from the time of its launch to the world’s press in the USA at the start of 1975 – and because the US market was so important to British Leyland, the usual process of final testing and honing was dropped in order to get the car on sale as early as possible. The decision was also taken to launch the Triumph TR7 in the USA only, European and British cars coming on stream later, once production could be ramped-up in order to meet demand. The onus was now very much on the Speke workforce in order to produce the car at an acceptable level of quality – reputations were built on first impressions and if the car was built well, the positive image would remain with the car throughout its life. Sadly, it was inevitable that they did not.

Technically, the car may not have been exactly ground breaking, but there were a few points worth lauding the car for at the time of its launch. Safety was big news and the TR7 was designed very much with this in mind; the monocoque had been designed to meet all upcoming US crash regulations and intelligent detailing in the structure meant that the car would prove to score well in passive safety terms. Although it appeared that the car incorporated an integral roll-hoop, it did not – but rear three quarter pillar was immensely strong, thanks to the box sections incorporated within, all the way up to the roofline and a cant rail over the windows.

One interesting aspect of the crash structure, (and one that marked the car as being ahead of the game in this respect) was that the front section of the bodyshell did not contribute much in the event of a head-on collision, but merely acted as a crumple zone; the major energy in such a collision was in fact absorbed by the wheels against the bulkhead and the engine against the scuttle. It may seem bizarre now, that the movement of the engine in the event of a collision was a desirable state of affairs, but because the scuttle are affected intruded very little into the seating area of the passenger compartment, it was not considered to be an undesirable trait. The strength at the front of the car was also aided by its X-shaped front subframe and its less-than-pretty 5mph bumpers which were made from box-section steel and covered by self-skinning methane foam.

Bodyshell strength was also above average for the time (but not in the class of the ADO17 saloon) at 7500lb ft per degree, but it was not the safety or strength of the Triumph TR7′s body that drew comment, but its style. In an amusing tale that has now entered into the folklore of motoring history, it was Giorgetto Giugiaro that summed up the feelings of many people: On his first viewing of the car at the Geneva motor show in 1975, he is said to have paused to take a long look at the TR7. Pondering its styling, he is said to have looked at it in a puzzled way and then walked around the car, only to say, ‘Oh my God! They’ve done it to the other side as well.’ This was no doubt a reference to the fact that in the development of new model styling, often different styling solutions are tried out on both sides of a clay model of the car – and Giugiaro obviously thought that the TR7 looked so bizarre that it could in no way be a production car!

It is easy to take cheap shots at the styling of the Triumph TR7, but alongside the Leyland Princess, it certainly showed that BLMC were keen on producing interestingly styled – bold – designs. It is just a shame that other factors conspired to play against the success of these cars before they had a chance to establish themselves on the market.

Early quality niggles were not evident at the time of the launch of the Triumph TR7 and because it was an export-only car, the US journalists were reporting on the car a full year ahead of their counterparts on the domestic market. The launch passed off without hitch and generally the US press were impressed with the car, if a little unimpressed with the ‘challenging’ styling. There were certainly no complaints regarding the handling and ride of the TR7, but what impressed even more than the chassis was the comfort and habitability of the passenger compartment: it was certainly viewed as a much more civilised car than its predecessors.

Because of the strict emission laws that were in force in the USA by 1975, extensive anti-smog equipment was installed in the TR7 and the 8-Valve 2-Litre engine, which was not exactly the most powerful engine to start with, suffered badly from the resultant power loss. In the USA, the TR7 was offered in two states of tune in order to meet the varying emission regulations within the country: 90bhp from twin-Stromberg carburettors in 49-State tune and a paltry 76bhp in single-carburettor California tune. In reality, this fact demonstrated that British Leyland had no suitable ‘federal’ engine in their line-up and they were suffering as a result of this. The result of this was that the American press called for a hike in power, something that British Leyland knew was in the pipeline.

May 1976

TR7 launched in the UK

One of the most impressive parts of the Triumph TR7 was its interior, which proved to be spacious (for a two-seater) and stylish in its execution. This early UK-specification did without the US style steering wheel, with its large and clumsy central crash pad. What is also evident from this picture is that its interior architecture owed nothing to its sports car predecessors or its saloon car stable mates.

The UK had to wait until 19 May 1976 for the TR7 to go on sale and the press generally treated this date as the time to treat it as a new model launch. Various detail changes were made to the TR7 in order to be more suited to European buying tastes – not least the use of smaller rear bumpers and an engine that was not strangulated by USA anti-emissions equipment: The higher compression, twin-SU version of the engine was used, producing a more realistic 105bhp. This gave the car more class-competitive performance with a (Triumph-claimed) 0-60mph time of 9.4secs and top speed of 110mph, as opposed to 11secs and 107mph of its Federal cousin. Of course this was easy meat for the 3.0-Litre Ford Capri, but British Leyland had thoughtfully decided to launch the TR7 at a competitive price of £2999, which was some £696 (or in these pre-inflationary times, over 20 per cent less).

AUTOCAR magazine reported on the car at the time of the UK launch and came away impressed with the car as a whole, but as always there were certain reservations. ‘Performance-wise, the TR7 is no sluggard. It tries hard, a little too obviously, and is great fun in the tighter country road that is its favourite going. On motorways and wide, gently curving roads, its sporting pretensions are not backed up with quite enough power’. Again, the chassis was praised for being greater than the sum of its parts and overall, they came away pleased: ‘… it will find a wider public when they hack off the lid and give it a soft top’. ‘When the TR5 appeared, a monthly fringe-contemporary described it as ‘an engine in search of a chassis’. The TR7 is sort of revenge for that remark, or at any rate, a reverse – a chassis in search of an engine.’

October 1976

Speke workers go on strike, ultimately leads to the factory closing and the cancellation of Lynx

In October of that year, Speke workers went on strike – and the end result of this was that any modifications that the company did try and incorporate into the TR7 could not be added. No one was building the cars. Those that were coming off the production line at Speke were proving to be suffering from indifferent build quality – and as a result were afflicted by the same, depressing reliability issues that also affected the products of Longbridge and Cowley. As we have seen, the net result of all this strife was the closure of the Speke factory and the moving of the TR7 production line to Canley, near Coventry – this disruption to production cost the company dearly and as a result, people who would have bought the TR7 in 1977 and 1978 were sadly forced to look elsewhere. It took time to transfer the production line and then further time to get the Canley line up to speed.

May 1978

Production moves to Canley

Apart from the death of the Lynx and the TR7 Sprint, the Speke closure also marked the end of any further serious development of the car. Michael Edwardes was concentrating the company’s efforts on ensuring that what little money was being given to the company by the Government was channeled into the development of the LC8 and LC10 hatchbacks. Luckily, the V8 version of the car was nearing completion at this time – and because the US market demanded this model, its future was assured. Also in 1976 and as a result of the fact that the impending ban on convertible cars in the USA proved to amount to nothing more than a scare story, work began on producing a drop head version of the TR7 ‘coupé’. Again because of pressure from the dealers in the USA and the fact that development of this car was nearing completion and proved to be relatively inexpensive, its future was also assured.

Once Canley did get up to speed, the improvement in the Triumph TR7 became immediately apparent: the quality of final assembly was of a higher order and a small round of changes was made to the car, including the fitment of the 77mm five-speed gearbox from the Rover SD1 and cosmetic improvements, such as the widening of the range of colours, a smartening of interior trim and the addition of a bonnet power bulge – in anticipation of the upcoming TR8. The opportunity was also taken to incorporate running changes to the car, with the upgrading of the electrics, instrumentation and cooling – all part of the standard running changes that would come part and parcel during the production run of any car, but in the case of the TR7 and all the strife at Speke, the company were unable to implement.

The convertible version appeared soon after in May 1979 – but again, disappointingly for customers in the UK and Europe, its sales were limited to the USA. It was immediately apparent to all, that in this form, the styling was everything that the TR7 should have been right from launch – so right were its lines. No longer was the ‘turret top’ an awkward looking car, but it has gone through the transition to become a pretty and striking open-topped car. At the same time, the TR8 also entered pre-production at Canley and a few of these models were in the hard-topped bodyshell, but sensibly, when the pre-production run became series production, the TR8 was offered only in the convertible body style.

The structure of the bodyshell was strengthened in order to compensate for the lack of roof – an additional strengthening box section being installed behind the seats, which linked the B-posts together. Extra strengthening was also added to the quarter panels and, curiously, BL engineers also incorporated an end-weighted front bumper, which was an expedient to lessen the effects of scuttle shake. Because of thoughtful design and against subsequent trends, the drop head version was slightly lighter than the fixed head version.

May 1979

Convertible version launched

1980 heralded the introduction of the Triumph TR8, but unfortunately for British Triumph fans, it was made available in the USA only. Strong and smooth Rover V8 engine allied with the convertible body style made for an extremely appealing car – a kind of latter-day MGB-V8, in fact. Performance and economy were excellent and the aluminium alloy engine was perfectly suited to the job of being the power unit for a ragtop. TVR would make a good living through building such cars in later years.

The USA market recovered as a result of the launch of the convertible model, but it could not have come at a worse time, as the World slipped into global recession following the Iranian crisis in 1979. This factor alone did not affect the sales of the Triumph in the USA, but when the exchange rates moved in favour of a strong Pound, it certainly affected the profitability of the company’s sports cars in the USA. When the TR8 went on general sale in the USA in May 1980, it was met with unanimous praise, being hailed as nothing less than the, ‘Re-invention of the Sports Car’, by Car and Driver magazine.

March 1980

Triumph TR7 convertible launched in the UK

When the convertible was launched in the UK in March 1980, it was also greeted with enthusiasm by the motoring press. Motor magazine might have been more reserved than their American counterparts, but they concluded in their road test that, ‘BL’s long-awaited TR7 drop head represents a significant development over the fixed head version. Lively performance with plenty of mid-range torque with long legged fifth gear.’ In their hands, it had also proven to be slightly quicker and more economical than the hard-topped version. What the British were denied though, was the TR8 version, of which the Americans received the lion’s share of the 2715-unit production run.

Thirty-five were produced in UK specification, but unfortunately, events overtook the TR7 family of cars and if this glowing report from Car magazine in December 1980 is anything to go by, we were short changed:

‘I asked myself more than once the deadly serious question: ‘would I spend my own hard-earned money on a TR8?’ This is not a fantasy. This car is expensive by American standards, and yet no more than a Mazda RX7 or a Datsun 280Z, and a lot cheaper than comparably equipped GM Corvette. And all round it will outperform them all. ‘Decidedly yes’, I answer each time.’ In conclusion, ‘When the TR8 is launched in Britain next year there will be nothing in its class to touch it, save perhaps the Porsche 924. But don’t expect to be able to buy it for what the Americans pay, even though the British model (without the emission control equipment) will be considerably cheaper to make…’

May 1980

Production transferred to Solihull

Late in 1980, production of the TR7 and TR8 was moved, yet again, to the relatively new Solihull factory, South of Birmingham to be produced alongside the Rover SD1. In reality, this move, which had spelled the death-knell for car production at Canley also proved to be the death knell for the Triumph TR7 and TR8 itself, because Michael Edwardes had plans on the cards to put this massive factory on ice.

In May 1981, BL made public their plans to kill the TR7, but Ray Horrocks made it clear that production could be continued if demand for the car improved ‘significantly’. Needless to say, it did not – stockpiles of unsold TR7s mounted up and as a result, the closure of Solihull went ahead, a further 3000 jobs at BL were lost, as well as resultant losses at the Speke and Swindon body pressing plants and the closure of the Wellingborough foundry in Northamptonshire.

October 1981

Production ended

Sports cars no longer figured in the plans of the company and even though the Abingdon factory was being wound-up at the same time and demand in the USA for the MG sports cars was still reasonably buoyant, (although down by almost fifty per cent since 1977) the agreeable option of moving TR production to Abingdon and introducing the MG Boxer was not taken.

Would the MG-badged, O-Series powered Boxer or the Broadside family have sold any better? Evidence would suggest that it may have sold enough to buoy the company enough to make it to the good years of the late-’80s: at the time of the MG closure in 1980, American dealers pleaded directly to Michael Edwardes to save the marque – and produced an order book full of unfulfilled orders for MGs. Certainly, using the O-Series engine would have trimmed costs; rationalisation always does – as would the fact that without question the Abingdon factory was unique in the company during the ‘dark’ years in the fact that their work force did not resort to industrial action and enjoyed a good relationship with their management – thus, there would not have been anywhere near the same level of lost production due to strike action.

Driving Triumph TR7 and TR8 (1975 – 1981)

It’s funny how how when we talk about Great British sports cars, few of us remember to mention the Triumph TR7. With almost 115,000 examples built during its all-too brief production run of six years and three factories, it was hardly a commercial failure – and today, there’s great specialist and parts supplier support. So why then, is the TR7 so overshadowed by the likes of the MGB and Triumph Spitfire?

It’s an interesting question, and one that’s going to take a lot of answering. The life and times of the TR7 was pretty traumatic, as they were overshadowed by political and industrial strife. Which is a shame – because if things had panned out, the TR7 would have ended up replacing all previous Triumph and MG sports cars, and gone on to enjoy lucrative times being the UK’s only viable sports car throughout the 1980s. But it never happened, and what’s left is mere conjecture.

But what of the car itself? Like all of Harris Mann’s creations at his time in the Longbridge hot-house, it certainly looked bold and interesting. But unlike the mainstream Allegro and Princess, the TR7 was underpinned by sensible Spen King engineering, so it could be reasonably argued that the package the TR7 presented to customers should have been the best of both worlds.

About the Triumph TR7

When the TR7′s styling and packaging were honed, the two benchmark sports cars in the USA were the Datsun 240Z and Porsche 914. Compared with the beauty of the first of these two cars, the Triumph’s styling must be seen as a failure – but then, compared with the Porsche, the TR7 did look rather good. The problem with its styling is a reflection of the shifting moods of the legislators at the time – as a targa or convertible, the TR7 looked quite good, but BL simply didn’t have the confidence to take a risk, and produce anything other than a closed car.

And by the time the first US dealers caught their first glimpse of the car in late 1974, it was clear that the threat to the open-topped car as a breed had already passed. But this notwithstanding, the TR7′s looks weren’t all that bad, and they certainly remain interesting to this day. Yes, it was dominated by those impact-bumpers (which were better resolved than some of the opposition, most notably the Fiat X1/9), and that gave it extra length, which then led to a gawky short-wheelbased, high-riding stance, that wasn’t truly fixed until sometime later with the arrival of the convertible.

Under the skin, it was a conservative affair, but also a bit of a delight for BL fans, thanks to its shared DNA with the ill-fated Triumph SD2 and Rover SD1. So, that meant MacPherson struts up front and a well-located live axle at the rear. The engine was effectively an eight-valve version of the Dolomite Sprint, pushing out a relatively modest 105bhp, and the emphasis was on easy drivability and a roomy, usable cabin. All of these objectives were met. Despite meaning that a standard TR7 is hardly sporting to drive. But on today’s roads, a well-presented and cared-for TR7 turns heads.

On the road

The TR7 is a suprisingly relaxing car to drive, and that’s down to the torque delivered by relatively large and unstressed engine. As you might expect, it’s smooth enough, but hardly thrives on high revs, delivering more than plenty of acceleration on part throttle and early-ish upchanges. On today’s mean streets, it keeps up with the flow, but that requires work – and that means going beyond the 4000rpm smoothness threshold. On the motorway, and in long-striding fifth, the TR7 cruises very calmly indeed.

Like the Rover SD1 and (presumably) the SD2, the TR7s is an accurate handler with relatively compliant ride quality (compared with the other three) and is probably greater than the sum of its parts. In standard form (and there’s so few like this left), the TR7′s handling balance is geared towards understeer, but there’s enough torque and throttle response to drive through this – if this is your bag.

The TR7's cabin is excellent, assuming you’re after a two-seater. The driving position is first rate, the seats are comfortable, there’s plenty of oddments space, and the controls and dashboard are the most effective of the lot (for instance, it has heating and ventilation that just works). We’ll go further – as long as you like the tartan seats (and we’ll assume you do, because you’re here), then the TR7′s interior also looks the best, and is certainly the classiest.

Just because it's modestly powered and not particularly heavy, don’t expect to blown away by the TR7’s fuel consumption figures, unless you’re the sort who drives your sports car in an unsporting way. At the pumps, the TR7 will average around 25mpg – but on a run, that's markedly improved.

When it comes to parts and servicing costs, the TR7 is pretty much the classic to beat. Availability is almost total, while very few garages will turn away a TR7 due to its simplicity.

Verdict

The Triumph is one of those cars that’s good at what it does, but can be improved significantly by its owner. One only needs to see the number of Sprint- and V8-engined conversions still in regular use to see that.

But that's the joy of the TR7: it can be what you want it to be. It's a car that can be modified to suit your needs – if you want a 16V screamer, buy a Sprint powered version, but if V8 touring is more your thing, grab a TR8 or more likely one of the aftermarket TR7 V8 conversions. And keeping it on the road is a doddle, too. Parts availability is brilliant, as is club and specialist support, making this one of the most sensible yet rewarding sports car purchases you are ever likely to make.

Forget the styling, as you either love it or hate it, but as classics go, TR7s are fantastic and great value. They're easy to work on, nice to drive with a little bit of work, and surprisingly practical for two. Even the basic car is quick enough to keep you amused, and the handling and steering are more than adequate.

Triumph TR7 and TR8 (1975 – 1981) Buying Guide

Good

Like fine wine, the TR7 has just got better and better with age. What looked gawky in 1975, now comes across as bold and daring-to-be-different. And those engine problems from new have long since been ironed out – with off-the-shelf cures readily available. Handling is easily upgraded, especially on the chassis side where uprated bushes and dampers can absolutely transform the TR7's ability to go around corners. As for power – tuning the 2-litre slant-four might not produce scintillating results, but the addition of a Sprint or V8 engine (both of which are popular conversions) add a great deal of fun into the mix.

Bad

- Get a bad TR7 and you'll be forever battling rust and 'Prince of Darkness' electrical gremlins.

- You'll not trust it when the weather turns bad, either.

- Also, the handling suffers terribly if the suspension components aren't in tip-top condition.

- A poor one will struggle to be worth what investment you put into it.

Watch

- Engine: cylinder heads warp, so take the car for a long test drive and make sure it doesn't get hot or misbehave.

- Check for traditional signs of head gasket damage such as mayonnaise under the filler cap.

- Bodywork: Screen surrounds are a notorious corrosion weak spot, so closely check for paint and trim issues.

- Transmission: Listen for axle whine on the move and check differential oil level if possible. Five-speeder can be notchy when cold, but frees up after a few miles.

- Check for automatic gearbox smoothness – but all units basically reliable.

- Sills: Inner and outer sills are extremely susceptible to corrosion, so make sure that they have been repaired properly, and not using cheaper cover sills as these will cause issues within a year of being fitted.

- Boot: lift the carpet and closely check the spare wheel well. Remove the spare wheel if necessary and make sure there's no trapped water. All drainage holes should be clear.

- Suspension: Straightforward and all parts readily available, but a known weak spot are the trailing arm mounting points, which can corrode. Very difficult to check for without a ramp, but an essential inspection point.

- Roof: Many Webasto parts are no longer available so make sure sunroof is in good working order.

- On convertibles, hoods are readily available and inexpensive, but check condition of all fixings are rear screen.

- Electrics: Check all electrical equipment works – switches, relays and wiring are all known to be flaky with age. If they have been fixed, make sure OEM – or better – equipment has been used.

- General points: Check paintwork repairs aren't hiding filler; Oil leaks are expected and part and parcel of TR7 ownership; Do the engine and chassis numbers tally up; is the interior in one piece as in many cases, trim is NLA

- If the chrome trim looks uneven it could well be that water has got in between the screen and A-post.

- Pop-up headlights: Mechanism is basically sound, but the switch or relay can be troublesome, leading to the infamous TR7 wink. Sorting it should be straightforward with off-the-shelf parts.

- Upgrades: all of these are desirable, so check when looking - Poly bush suspension kit,Roller top mount bearings for the front struts, Uprated discs and pads, Uprated brake servo, four-pot calipers, Rear disc kit, Remove the damper weights in the bumpers, Remove the viscous fan and replace with an electric one

Running Triumph TR7 and TR8 (1975 – 1981)

Clubs

- TR DRIVERS' CLUB +44 (0)1562 825000

- TR REGISTER www.tr-register.co.uk

Specialists

- Canley Classics: www.canleyclassics.com

- David Manners: www.jagspares.co.uk

- Rimmer Bros: www.rimmerbros.co.uk

- Revington TR: www.revingtontr.com

- Robsport: www.robsport.co.uk

- TRGB: www.trgb.co.uk

Triumph TR7

| 0–60 | 9.0 s |

| Top speed | 109 mph |

| Power | 105 bhp |

| Torque | 119 lb ft |

| Weight | 1000 kg |

| Cylinders | I4 |

| Engine capacity | 1998 cc |

| Layout | FR |

| Transmission | 4M/5M/3A |

Triumph TR8

| 0–60 | 8.0 s |

| Top speed | 120 mph |

| Power | 155 bhp |

| Torque | 198 lb ft |

| Weight | 1150 kg |

| Cylinders | V8 |

| Engine capacity | 3528 cc |

| Layout | FR |

| Transmission | 5M |

.jpg?width=640&height=426&rmode=crop)

.jpg?width=640&height=426&rmode=crop)

.jpg?width=640&height=426&rmode=crop)

.jpg?width=640&height=426&rmode=crop)

.jpg?width=640&height=426&rmode=crop)

.jpg?width=640&height=426&rmode=crop)