- Reviews

- Best Classic Cars

- Ask HJ

- How Many Survived

- Classic Cars For Sale

- Insurance

- Profile

- Log out

- Log in

- New account

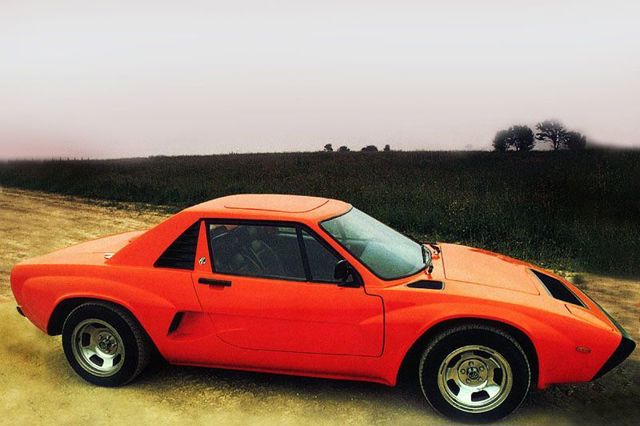

AC 3000ME (1978 – 1985) Review

AC 3000ME (1978 – 1985) At A Glance

The 1970s were a bit of a dry spell for AC. After the glory years of the Cobra and to a lesser extent, the 428, the company busied itself developing a more affordable - and modern - sports car. The 3000ME ended up hitting the market late and selling in disappointing numbers, but it now has a devoted following. AC decided that mid-mounting a Ford V6 transversely over a custom-made transmission, and clothing it in a good-looking glass fibre body that had originally seen the light of day as a kit-car concept.

That was one problem: the engine’s heavy weight and less-than-sporting output meant only 120mph and 8.5 seconds to 60mph. After the V8 monsters of before, that wasn't enough. Delays in going into production meant the 3000ME was pitched against the similarly-priced Lotus Esprit. Volume sales never materialised, with around 100 built, including a short-lived revival in 1984-85 when licensed to a Scottish factory. High survival rate and low overall value means it's a great classic opportunity - still.

Model History

- October 1972: Bohanna-Stables Diablo concept car was show - AC decided to buy the rights

- January 1973: AC started working on the prototype 3000ME

- October 1978: AC 3000ME went on sale at the British motor show

- July 1980: Ghia showed its rebodied AC-Ghia concept car

- June 1984: AC 3000ME production moved to Scotland

- November 1985: Production ends as the receivers are called in

October 1972

Bohanna-Stables Diablo concept car was show - AC decided to buy the rights

It started with a concept. And that was sired from an idea. Which was borne out of competition. Yes, like all good cars in life the AC 3000ME might have endured something of a convoluted path to production, but there’s real pedigree in its conception.

The creative thinking that lead eventually to AC’s controversial mid-engined sports car was directly influenced by the motorsport success of the Ford GT40 and Lola T70 – Robin Stables, former racing mechanic and Lotus dealer teamed up with ex-Ford AVO man, Peter Bohanna, to come up with the Bohanna-Stables Diablo concept.

The Austin Maxi 1500-engined mid-engined sports car was unveiled at the 1972 Racing Show in London, and immediately drew favourable comparisons with Italian exotica, such as the Dino 246GT and De Tomaso Mangusta. But the delicately styled concept car was far more than a pretty body, because Stables and Bohanna – both freelance engineers and designers who’d spent more than their fair share of time working at Lola – ensured that the engineering that underpinned it was thoughtfully conceived, too. It featured independent coil springs and wishbones all round, subframes front and rear, and a rigid tub structure – this was clearly a car that lacked backbone.

After the show lights had died down, it was clear that Stable and Bohanna had produced a very desirable car, one that looked like it could add something to the UK specialist car market. AC’s Keith Judd certainly believed so, and after speaking to the car’s creators, he drove it over to the AC Cars factory in Thames Ditton and presented the car to company boss, Derek Hurlock.

January 1973

AC started working on the prototype 3000ME

Bohanna-Stables Diablo concept looked impressive enough to convince AC management to put it into production…

Initially, Derek Hurlock wasn’t convinced that AC needed the Diablo. He felt that the car didn’t fit the company’s values. But more than that, there were issues about the engineering – just how much work would it take to turn this car into a production model. He said, ‘They were so enthusiastic about the idea… I don’t think we realised at first how much would have to be changed.

It started virtually as a spaceframe chassis. As time went on Alan Turner and Bill Wilson almost completely reworked it.’ Of course, the company had been here before with the Tojeiro racing chassis it adopted, but which needed re-developing almost entirely to become the 428… and there wasn’t a lot wrong with that.

There was also the issue of its styling, which Hurlock believed just wasn’t that special. But despite these misgivings, Hurlock trusted his team implicitly, and agreed to go ahead with the new car, buying the rights to the Diablo from Bohanna and Stables before promptly retaining them to undertake some of the development work needed to get the car into production.

The initial goal was to launch the new AC at the 1973 Earls Court Motor Show. This was ambitious – and BL didn’t help by refusing to supply E-Series engines to AC, stating that Cofton Hackett would be at full capacity come the arrival of the Allegro, and there would be nothing spare for AC. It wasn’t the blow it might have been, though. The tuning potential of this compact engine wasn’t realised at the time, and given that AC had lofty ambitions also when it came to pricing, the decision was taken to drop in a Ford Essex V6, staple of the Granada and Capri, and give the car a little more push. The pushrod V6 might not have been state of the art with 138bhp on tap, but it was an easy fit in the car’s engine bay and most importantly, extracting power from it was relatively simple.

The Maxi’s engine was chosen because of its transmission-in-sump layout, facilitating packaging. So to gain a similar advantage from the Essex V6, AC’s Bill Wilson designed a new gearbox that sat under the engine and was driven from the crank by chain. This was no simple matter to engineer, even if standard Hewland gear clusters were used, and as a result, the production date moved back.

The car did make its debut at Earls Court in ’73 under its new name of AC 3000ME. The press loved it – and celebrated its high quality glassfibre/steel perimeter chassis construction. The details looked good, too: styling was lauded, as was its spacious interior and open-gate gear selector. It was a taste of Ferrari from Thames Ditton. The price wasn’t confirmed – although AC management hinted that it would be between £3000-4000, and that deliveries would begin in July 1974. How wrong they would prove to be…

By 1974, the styling was finalised. The shape of the Diablo was retained with some modifications to the nose, a higher roofline, and improved air intakes design. AC’s engineers worked hard to get the 3000ME into production. Derek Hurlock said, ‘All was well in hand. Then out of the blue Type Approval hit us.’

The car failed its crash test, and that led to changes to the structure and underpinnings were needed to be engineered in order to allow the car to pass, a time consuming process. Development was an expensive process, and with the company beginning to be affected by the energy crisis, and with production of Mobility Trikes keeping things ticking over, the new car project began to lose impetus.

Throughout the ’70s, the AC 3000ME would appear at motor shows, but deliveries were no longer being promised. By 1976 and with 1200 orders in its pocket, finances were getting tough, and money to continue the car was becoming harder to find – especially as it had an unusually high bespoke content.

October 1978

AC 3000ME went on sale at the British motor show

Under the skin, and the AC 3000ME is excellently packaged.

After six years and well over £1m in development costs, the AC 3000ME went on sale at the 1978 NEC Motor Show. If enthusiasts weren’t as excited as they might have been back in 1973, they were certainly breathing a collective sigh of relief that the car had been introduced at all. Inflation had thrown the original ’73 anticipated price of £3000-4000 out of the window, but the £11,300 list quoted the following year put the car among some very talented opposition.

But it was good to have AC back in the new car price lists after a six-year absence. The first production car rolled off the line in 1978 (there were 11 prototypes before that), and the initial reactions in the media were very positive indeed.

But it took time for the road testers to get their hands on the 3000ME – mainly because the company was struggling to meet demand for the new car. By the time Autocar magazine ran its first road test in March 1980, the price had jumped yet again to £13,238. To put that into perspective a (155bhp) Rover 3500 V8-S Cost £11,287, a (160bhp) TVR Tasmin cost £12,800, (170bhp) Porsche 924 Turbo £13,629, and the (160bhp) Lotus Esprit 701 £14,175. Somehow, the AC’s 138bhp just didn’t seem enough in such exhalted company.

Autocar gave the 3000ME a reasonable review, though, praising its practicality and low fuel consumption. The roomy cabin was also a positive point, ‘earning top marks for for superbly efficient use of space.’ But there were issues that meant that the magazine concluded that the car was ‘so nearly there…’ Traction and brakes may have been superb, but performance was feeble compared with the opposition (0-60mph in 8.5 seconds and a top speed of 125mph), and the handling at high speeds suffered from the jitters – ‘…doubly frustrating because in so many other areas, it’s such a well-sorted car.’

But that’s the story of the AC 3000ME – what might have been.

Styling had barely dated between the original launch in 1973 and the 3000ME’s 1978 production start.

The lack of performance could have been so easily resolved – at a cost. Robin Rew’s Silverstone-based tuning company ended up turbocharging 19 customer’s cars – thereby releasing the potential of the Essex V6. The expert hillclimber and ex-engineer, photographer and PR man’s Rooster Turbos were neatly installed and using an IHI blower, produced a much more realistic 200bhp. The carburettor was retained in this installation, but an intercooler was added so boost levels of 6-9psi could be run. Rew tried to convince Derek Hurlock to consider adopting this conversion on the factory cars, but he was having none of it.

Other improvements sorted out the car’s only other real problems – carburettor flooding was sorted by fitting a new manifold that repositioned it. As for the handling foibles, Rew altered the rear wishbone pivots to add some much needed toe-in. Stability and predictability were the results.

July 1980

Ghia showed its rebodied AC-Ghia concept car

Perhaps another missed opportunity was the vague possibility of joining forces with Ford. Ghia studios in Italy headed by Filippo Sapina produced the sensational AC-Ghia, and touted it around the motor show circuit in 1980. Although there was little wrong with the styling of the 3000ME, it was clear that the Anglo-Italian iteration was far more forward looking, as well as usefully more compact. Sadly Derek Hurlock was far from amused by the Italian car, and conversations between AC and Ford would have to wait for another day. Sapina had the car built up, and used it on the road – and it was tested by Car magazine in 1981, who decided that it was pretty much the second coming of the sports car…

…except that in reality, the car was never really considered a production possibility, and any idea that Ford would want to take this rallying in the wake of the failure of the Escort RS1700T debacle were soon put to bed when the RS200 made an appearance a couple of years later. However, there’s no arguing that it’s aged very well indeed.

The AC 3000ME certainly attracted attention from potential suitors though, and in the USA PanterAmerica, considered selling the car Stateside powered by a 2.2-litre Ford turbo engine, and sold with Carroll Shelby’s blessing. Nothing came of the plan, and only a single car was made in the end.

AC-Ghia concept based on the 3000ME’s running gear looked a million miles removed from its donor car, and it’s not hard to imagine it being in production today.

June 1984

AC 3000ME production moved to Scotland

Even as these schemes were being plotted in the USA and Italy, AC Cars in the UK was seriously beginning to struggle. Undoubtedly, launching a 3-litre car in 1979 was a very bad move – we were in the grip of the second oil crisis, fuel prices were rocketing, and we were heading towards a rather unpleasant global recession. So it’s unsurprising that AC was struggling to sell the 3000ME in anywhere near enough numbers to allow it to break even.

Even as these schemes were being plotted in the USA and Italy, AC Cars in the UK was seriously beginning to struggle. Undoubtedly, launching a 3-litre car in 1979 was a very bad move – we were in the grip of the second oil crisis, fuel prices were rocketing, and we were heading towards a rather unpleasant global recession. So it’s unsurprising that AC was struggling to sell the 3000ME in anywhere near enough numbers to allow it to break even.

In 1984 and After 76 cars had been built, Derek Hurlock decided that it was time to sell AC Cars, and looked around for a buyer. He had been suffering from failing health for some time, and knew that he was fighting a losing battle with the 3000ME. Scottish entrepreneur David MacDonald approached the family and made an offer for the production tooling of the 3000ME as well as the rights to licence the AC name with it, and soon settled on a deal that saw the production tooling including moulds and jigs heading north of the border.

The new company, AC (Scotland) plc, was established in a new factory in taken over from the Scottish Development Agency at Hillington in Glasgow. A further 30 cars were built, while development on an updated car was set-up. A prototype powered by Alfa Romeo’s excellent 2.5-litre Busso V6 engine emerged, followed by a nearly-complete Mark 2 prototype, but time was called on the venture in November 1985, when the Official Receivers were called in to close the company.

November 1985

Production ends as the receivers are called in

AC 3000ME

| 0–60 | 8.5 s |

| Top speed | 120 mph |

| Power | 138 bhp |

| Torque | 192 lb ft |

| Weight | 1130 kg |

| Cylinders | V6 |

| Engine capacity | 2994 cc |

| Layout | MR |

| Transmission | 5M |