- Reviews

- Best Classic Cars

- Ask HJ

- How Many Survived

- Classic Cars For Sale

- Insurance

- Profile

- Log out

- Log in

- New account

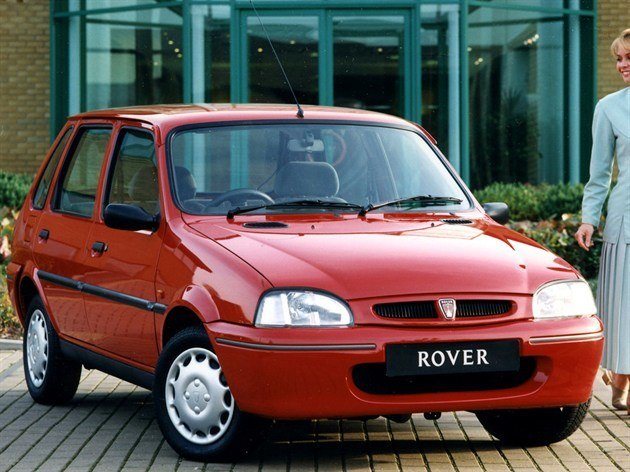

Rover Metro and 100 (1990 – 1998) Review

Rover Metro and 100 (1990 – 1998) At A Glance

The Rover Metro was announced to the world by its maker by one simple word: 'Metromorphosis'. It might have looked like the original, but thanks to all-new K-Series engines under the bonnet and intelligent suspension modifications, the Metro emerged as a class-leading supermini in 1990. To drive, it really was a whole new ball game, with sweet-spinning engines, supple ride and Rover 200 seats up-front with a re-angled steering column, for a big-car driving position.

Seven years on, and the facelifted Rover 100 was shamed out of sale thanks to a poor performance in the EuroNCAP tests, which did their best to scare off all sane drvers. Rover never replaced the Metro/100, expecting buyers to plump for the 200 instead - which didn't really happen as it panned out. But the Metro and 100 are both still good to drive, and there's an enthusiastic following for this little car that should ensure that the best ones will make it through to classic car status. Interesting models are the GTI 16V and Cabriolet - these are already on the up.

Ask Honest John

How much is a 1995 Rover Metro worth?

What were the differences between a Rover Metro Rio and the Metro Rio Grande?

Where should I sell my 1990 Metro?

Model History

- January 1983: Austin Rover starts work on project AR6, the Metro replacement

- January 1987: AR6 cancelled, replaced by the R6

- May 1990: Rover Metro launched

- January 0001: SMMT Sales figures 1990-1996

- January 1995: Rover Metro facelifted into the 100-Series

- December 1997: Rover 100 production ended

January 1983

Austin Rover starts work on project AR6, the Metro replacement

In the early stages of planning the AR6, there was a long held belief within Austin Rover that the Maestro and Montego would, at the very least, earn their keep – and along with the extra £1.5 billion inward investment from the government, the company believed that there would be sufficient funds to develop an entirely new supermini. The car quickly took shape – and following on from the lessons learned from the ECV3 concept car of 1983, it came as no surprise that the AR6 would sport such advanced features as flush glazing and extensive aerodynamic detailing, which had been carefully developed for the BL Concept car. Also in the small car’s portfolio was a light weight construction, which allied with the advanced engine being drawn up at Longbridge meant that therein lied a potential for startling fuel economy.

The aluminium bodied BL ECV3 of 1982 showcased many ideas that would eventually find their way into the AR6. Flush glazing, lightweight construction, space efficient interior and a 3-cylinger engine, which paved the way for the K-series engine, mark this out as a highly significant vehicle in the company’s history.

The aluminium bodied BL ECV3 of 1982 showcased many ideas that would eventually find their way into the AR6. Flush glazing, lightweight construction, space efficient interior and a 3-cylinger engine, which paved the way for the K-series engine, mark this out as a highly significant vehicle in the company’s history. Rear view shows the tapered flanks and very interestingly, the considered airflow underneath the car resulting in a smooth underside - and a diffuser-like arrangement at the rear, which created a low-pressure area at the rear.

Rear view shows the tapered flanks and very interestingly, the considered airflow underneath the car resulting in a smooth underside - and a diffuser-like arrangement at the rear, which created a low-pressure area at the rear.

Certainly, the AR6 was to have been a radical small car, which in the eyes of Harold Musgrove, was the ideal vehicle for the high technology image that he was chasing for the car division.

Unlike the Metro, the AR6 was devised from the beginning to be available in three and five-door – and along with the traditional idea of a long wheelbase within a short given body length, the interior packaging of both models looked exceptionally efficient. Certainly the ECV3, from which the AR6 was inspired, offered a tremendous amount of interior room – and the large glasshouse ensured that the ECV3 cabin was also a very airy place to sit. Definitely, Austin Rover executives were bullish about the AR6 and its chances in the marketplace, and much of the company’s development resources went into its gestation.

Throughout 1985 and 1986, development of the car continued apace, and several running prototypes were built, which were spotted pounding the Gaydon and MIRA proving grounds. The AR6 was reaching the stage of production readiness – all that was required for the final go ahead were the finances from within the company to bankroll the final stages of development. However, there was now a growing crisis of confidence within Austin Rover and it was becoming clear that because of the uncertainty over the company’s future and the government’s growing impatience at their stubborn refusal to show any form of profit, plans were drawn up for a lower cost alternative.

Unlike the AR6 project itself; the K-series engine was coming along nicely. Under the leadership of Roland Bertodo, the 1.1 and 1.4-litre versions were shaping up to be light and efficient power units – certainly worthy enough to replace the immortal A-series engine. Because the future of the K-series engine was assured (early on during its development programme, the decision was made to use it in the AR8 as well as the AR6), through necessity, a lower cost alternative to the AR6 was taking shape at Canley. Why was this so? Management and planners alike knew that the AR6 was always going to be an expensive project, and now that the government had made it clear that they were determined to sell Rover at the earliest opportunity – one thing not needed were the ongoing costs of development of the AR6, rumoured to be something in the order of £500 million, minimum – excluding the costs of the K-Series. Preparing a fall-back based on the Metro was therefore seen as something of a necessity, given the fact that Graham Day was reviewing everything in the product cupboard with microscopic attention to detail.

January 1987

AR6 cancelled, replaced by the R6

As expected, the axe fell on the AR6. Obviously, this decision was taken as a cost option – Graham Day’s regime could no more afford to engineer the advanced little car for production, whilst maintaining a reasonably the appearance of a healthy financial performance for any potential suitors of Rover. As it was, the Rover 800 was the only new product on offer or near to introduction at the time, which was in a position to be marketed as a premium branded product. It goes without saying that the decision to kill AR6, although a sound financial one was unquestionably a short-termist solution, and it caused much disappointment within Austin Rover, especially given the potential of the AR6.

Spotted testing in 1989, the R6 prototype could have gone unnoticed in this street scene

Spotted testing in 1989, the R6 prototype could have gone unnoticed in this street scene

Now that the replacement of the AR6 had been cancelled – this car’s replacement, the K-Series powered Metro facelift was given the go-ahead. The car was given the official development tag of R6 and the engineering make-up of the car was rapidly devised. Because funds were very tight, the existing car’s entire monococque would be used and changes would be made to it only where necessary.

Of course, re-engineering the Metro’s hull to accommodate the K-series engine and its end-on PSA-derived gearbox was not so straightforward. When mounted transversally, the unit would occupy more width of the car than the A-series, with its transmission in sump layout. Luckily, because the Metro was blessed with a stiff hull and a favourable accommodation/length ratio, it was easy to see that the engineers had a good starting to point to work from. Essentially, this meant that the R6 styling was well and truly stuck with the familiar Metro theme; the only room for movement was at the front, where the new front section was to be fitted. Roy Axe stated that the styling of the R6 should not be attributed to one designer, as it was a committee job… and perhaps given the nature of the overall “look”, this is probably the best way to view the R6.

However, it could have looked a whole lot better. Once the technical package was roughly set, David Saddington worked on a more comprehensively restyled version, using the R6 underpinnings. This car, known as the R6X (pictured below) was, essentially a more stylish version of the final car, and possessed, but sadly, it was cancelled due to lack of funds…

David Saddington's R6X had all the hallmarks of success...

David Saddington's R6X had all the hallmarks of success...

With the question of engine and gearbox choice answered, the only real headache that the R6 posed was what suspension system would be needed. When launched in 1980, the Metro’s Hydragas system gave it class competitive ride quality and handling – as well as a degree of “chuckability” that endeared it to its buyers. But times had moved on: the Peugeot 205 especially, had shown that smaller cars had grown, but also that small car ride and handling had become significantly more sophisticated. Because of these huge leaps and bounds made by the opposition, there were still unanswered questions on what was the preferable system to use in the R6: on one hand, work was completed on adapting the conventional set-up used in the AR6 for the R6, but as the Metro’s floorpan would require expensive (and extensive) re-engineering to accomodate the AR6 system, this was not an ideal solution. With this in mind, work also continued in-house on refining the existing car’s Hydragas set-up.

The driving position of the Metro had also been a constant source of criticism from the press as well as customers so work was also done on improving it. Although the body shell of the Metro would be used unchanged, engineers were given enough leeway to lengthen the nose of the car (improved engine access) and also move the front axle forward slightly. The net result of this was that the driver foot well was lengthened, the steering column could now be set as a more conventional angle and the front seats be set in a more natural position.

Swiftly, the configuration of the R6 was set: K-series engine, PSA gearbox, and a slight increase in wheel track, front and rear – only the suspension layout was yet to be settled. That is, until the homemade efforts of Doctor Alex Moulton were brought to the attention of Rover.

As the inventor of Hydragas (and Hydrolastic before it), Moulton was keen to demonstrate the benefits of his system: the suspension units were more compact, and therefore easier to package. Besides, Rover knew that in order to use a conventional system in the R6, a degree of re-engineering in the floorpan would be needed. As explained briefly in the Metro story, Moulton had modified his own W-registered Metro to accept front/rear interconnected Hydragas suspension.

Why front/rear interconnection as opposed to the vestigial side to side as it was on the existing car (“vestigial” meaning a small pipe interconnecting the two rear displacers, eliminating the “three legged stool” effect of zero-interconnected Hydragas – a decision taken out of safety consideration)? When the front wheel encounters a bump and rises, the suspension fluid will rush from the front suspension unit to the rear. The rear wheel will resultantly lower, lifting the tail of the car and allowing a level ride. Citroëns demonstrate this trait perfectly when encountering a “sleeping policeman” – the whole car rises in unison and suspension “see-sawing” encountered in conventional cars (and the original Metro) is eliminated.

Why this ideal arrangement was omitted from the original Metro can be best summed up by Moulton himself, “I was struggling to show how an interconnected Hydragas Mini, for all its diminutive size could give better results than a VW Polo. But BL’s Spen King, a very strong-minded and knowledgeable automotive engineer, didn’t like it. He preferred absolutely conventional cars. Yet I was persistently and consistently offering something superior in Hydragas.” In fact, the original Metro was so compromised by its non-interconnected Hydragas arrangement, that Moulton felt that at best, the solution would only produce a car that was average.

“All they’re doing is substituting the conventional spring and damper with a Hydragas unit” and that because of the compromise engineering in making this system work, needless complexity was designed in anyway, “Anyone coming in from outside would take one look, pronounce it burdened with nasty costs to no advantage and get rid of it.” Of course the real reason that Spen King adopted non-interconnected Hydragas for the original Metro was that the extra piping of the system employed on the Allegro and Princess would have cost extra money. So it was dropped – and it has to be said that the decision to do so was a rather questionable one. King himself recalled recently that, “we all had guns to our heads…”, which would go some way towards explaining the immense pressure he was under as the company’s Technical Director.

Doctor Moulton invited CAR magazine to drive his modified Metro, which they did… and they were stunned at the difference that interconnection made to the package. How Rover’s own engineers heard about the car is an interesting tale in itself: during July 1987, Moulton had received Sir Michael Edwardes as a guest at his house, and during the meeting, Moulton invited Edwardes to drive his interconnected Metro… like CAR magazine, Edwardes was very impressed, and he telephoned Graham Day up to tell him that they, “should incorporate the system and charge £100 extra for it!” Duly alerted about the existence of the Moulton solution, and allied with the painful decisions that the company had made over the AR6 and with question of the what the configuration of the R6 needed to be still to be unanswered, a viewing of Moulton’s solution would prove irresistible for Rover.

And so it was. Rover took the car away to Canley and engineers thrashed it around, before rapidly deciding that Hydagas did indeed have a great deal of life left in it and that following the example set by Moulton, with careful development, the system could be developed into a class-leading package. The decision was easily made: the R6 would be launched with Moulton’s interconnected version of Hydragas – and in taking that decision, Rover demonstrated that lateral thinking sometimes produced results far in excess of corporate compromise…

By 1988 road going versions were being tested and were delivering impressive results. Attention turned to marketing the car.

Rover was very aware of the fact that in the UK at least, the Metro was still a best-selling car and the name was still regarded fondly by customers. Following the fact that there were no cases of mass abandonment by their clientele following the deletion of the Austin badges from the cars’ boot lids during 1987, it became clear that the new car would become a Rover and not a “non-Rover”, as Kevin Morley used to refer to the Austin-era cars. At the time, the smallest Rover available was the 1342cc Rover 213, which although clearly a Honda-based car, was a popular choice with customers. It was, however, the smallest car to wear a Viking badge in living memory, and there was a sense of unease that there would be some buyer resistance to a Rover-badged supermini.

The decision for the car to adopt a Rover badge may have been reasonably straightforward – naming the model was not: On one hand, the Metro name may have been a known quantity in the UK, but it also pointed to an increasingly outmoded anachronism of a car. It also clearly, was linked with the old days… Consideration was also given to the fact that customers would see the car as a lightly revised Austin Metro, rather than the re-engineered new car that it really was. After researching many different options including, amusingly, “Metro, by Rover” the decision was made to call it the Rover Metro in the UK and the Rover 100 Series (111 and 114 models) in overseas markets, where being seen as an entirely new car would be no disadvantage.

May 1990

Rover Metro launched

By the May 1990 launch date of the Rover Metro, Rover was certainly on a roll: the 200/400 had been hailed a critical and commercial success and the 800 was undergoing something of a renaissance on the marketplace. In the backdrop of the 200/400 launch, Rover announced the new Metro, which incorporating Rover 200 front seats (which robbed rear seat legroom), trim and colours certainly was well received. Much was made of the K-series connection, knowing that much had been made of the new engine following the awards it won from the press and industry. If the press were disappointed at the styling of the new car – oh, so familiar inside and out, they found the driving experience something of a revelation.

At launch, the Metro GTa was the penultimate sporting model in the range: this brisk hatchback was powered by the 8-valve version of the 1.4-Litre K-series engine and served as a suitable replacement for the well-loved MG Metro 1300. Evident in this photo is the elongated front end and slightly lengthened wheelbase forward of the front doors.

At launch, the Metro GTa was the penultimate sporting model in the range: this brisk hatchback was powered by the 8-valve version of the 1.4-Litre K-series engine and served as a suitable replacement for the well-loved MG Metro 1300. Evident in this photo is the elongated front end and slightly lengthened wheelbase forward of the front doors.

An example of this was the verdict reported by What Car? magazine, who after testing the Rover Metro 1.1L against such luminaries as the Peugeot 205, FIAT Uno and their then Car of The Year, the Ford Fiesta pronounced an easy victor.

“The New Metro is a quantum leap, and on several accounts. For a start it’s light years ahead of its predecessor, far more so than its obvious family resemblance would suggest. But, more important still, it sets new standards of quality, ride and refinement for the class… In its chassis dynamics – ride and handling – it takes on the acknowledged masters of the art, the French, and beats them. It’s probably the quietest, smoothest, most refined car this side of £10,000 or even a bit higher.”

“Drive the Metro, and unless you need more space you wonder if you need anything grander. Our only reservation concerns the fuel economy, which really ought to be better.”

This enthusiasm was reflected across the entire UK specialist motoring press; Car magazine drove one on a 15,000-mile marathon and came away with nothing but praise, and Autocar & Motor declared it their new supermini “Hero”. If that praise sounded like blinkered jingoism, remember that the motoring press had become much more objective in their reporting during the 1980s, less afraid of pulling punches than they had ever been before – and seen in this light, the Rover’s achievement becomes all the more impressive.

Left: revisions to the rear end were limited to the adoption of a new tailgate, more stylish rear lamp clusters and full-depth bumpers. From the rear, the Rover Metro looked completely different to its progenitor. Right: Facia was largely unaltered from the 1984 vintage Austin Metro version, but was given a disproportionate lift by the new choice of trim colours, the rounded edges on the main instrument binnacle and the Rover 200-style safety steering wheel.

Left: revisions to the rear end were limited to the adoption of a new tailgate, more stylish rear lamp clusters and full-depth bumpers. From the rear, the Rover Metro looked completely different to its progenitor. Right: Facia was largely unaltered from the 1984 vintage Austin Metro version, but was given a disproportionate lift by the new choice of trim colours, the rounded edges on the main instrument binnacle and the Rover 200-style safety steering wheel.

Rover marketed the Metro as a completely new car, playing the Rover angle for all it was worth: “The New Metro, with Rover Engineering”, sub headed the memorable, “METROMORPHOSIS” catchphrase. Backed up by the expensive and impressive Ridley Scott television commercial, the new car soon caught the public’s imagination. Sales started extremely well – so well, in fact, that Rover was completely surprised by it.

Strategists within the company had thought that the Metro would have a short shelf life – and to a degree, this was true – and the fact that it was now smaller than all the competition, barring the Citroën AX, meant that it was going to have limited sales potential. The fact that the CVT automatic version (leaving the A-series powered Metro automatic to linger on for a further year) and diesel versions were not planned to arrive until long after the initial launch did nothing to detract from the early popularity of the car. Bearing this in mind, viewing the SMMT UK sales figures is extremely interesting, considering that at the time of launch, the Rover Metro was, effectively, a ten year old car.

January 0001

SMMT Sales figures 1990-1996

| 1990 | 1991 | 1992 | 1993 | 1994 | 1995 | 1996 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Metro/100 | 81,064 | 60,361 | 56,713 | 57,068 | 58,865 | 52,392 | 42,009 |

| Ford Fiesta | 151,475 | 117,181 | 106,695 | 110,449 | 123,723 | 129,574 | 139,552 |

As can be seen from the sales performance of the Rover Metro, it established itself and remained popular until 1995, when the Rover 100 was launched. Why this should be so is interesting and demonstrates that the Rover plan to replace the Metro in 1995 by the R3 (Rover 200) would have been the correct thing to do in order to maintain market share. Of course, the company’s market share in the UK held no immediate concern to George Simpson and his replacement, John Towers, who both felt that the profitability of Rover was of the utmost importance.

Of course, this is true, but this should not have led to the error in judgement that led to the company’s strategy going off-course – and producing the Rover 100.

Rover agonised over how to replace the Metro because on one hand, the limited profitability of superminis and the fact that the company were producing approximately 500,000 cars per year meant that it would be desirable to produce primarily bigger, more profitable cars. By 1992, Rover were deep in the throes of devising a viable supermini strategy: they were developing R3 on one hand, but at the same time with that car’s slow move upmarket, something needed to be done about the direct replacement of the Metro. Did it need to be replaced? The finance men argued against, the strategists argued in favour, talking in terms of maximising market share.

In the end, the decision made was to replace the Metro with the Mini replacement that was in the early throes of development, move the R3 into the Golf/Escort market and the HHR into the Mondeo/Cavalier market.

January 1995

Rover Metro facelifted into the 100-Series

Metro becomes the 100 series: very little changed from the 1990 Metro apart from a slightly smoother looking front end. Contrast this with the prototype, shown above.

Metro becomes the 100 series: very little changed from the 1990 Metro apart from a slightly smoother looking front end. Contrast this with the prototype, shown above.

So, in January 1995, the Rover 100 was launched to the disappointment of the press and public alike. The problem was that the styling was not changed nearly enough – the grille (basically a version of the pre-1994 R3 prototype) and headlights were smoother, but apart from that, the Metro was unchanged. Many people were expecting more – and by 1995 with the advent of such cars as the FIAT Punto and SEAT Ibiza, which had moved the game forwards yet again, the Rover 100 had nothing left with which to compete with this next generation.

No doubt that this was a sad turn in events, because the Rover 100 still possessed the fine engine, interior ambience and (front) seating that it always did – but in this most fashion conscious of markets, the looks simply no longer cut the mustard.

Sales resultantly dwindled, but as this was planned for, Rover was not too concerned: they had decided that the Metro would be allowed to die a natural death, after all, the Mini would in theory be hitting the market around 1998/1999, by which time the Metro could be honourably retired after a long and successful run.

December 1997

Rover 100 production ended

Unfortunately, even this plan was scuppered at the hands of Euro NCAP (The European New Car Assessment Programme) – who reported in their crash test of the car that it fell a long way behind what was considered a minimum standard in passive safety. In fact, it was given a one-star front and side impact rating, which was, essentially, a disastrous showing. Unfortunately for Rover, this story became a lot more widespread than the specialist press and it transcended the usual car magazine into the daily newspapers. Worse, the Rover 100’s performance made it to the early evening news on the BBC…

Needless to say, this was disastrous for Rover and within days, orders for the car dried up. Rover was given no choice other than to withdraw the 100 from sale with production ending on December 23, 1997.

Needless to say that this was an exceptionally sad end for a car that had begun so promisingly back in 1990.

Rover Metro and 100 (1990 – 1998) Buying Guide

Good

- Decent new K-Series 1.1 and 1.4 engines.

- End-on gearbox and up to 5-speeds at last.

- Front-end rust traps largely eliminated.

- Better built than Austin Metro and generally reliable.

- Simple CVT auto originally worked well - far less troublesome than Ford and Fiat CVTs.

- Comfortable. I've done 450 miles in a day in a Metro CVT.

- Decent fuel consumption.

- Iron block 1.4 TUD diesel engine comes from Citroen AX and Peugeot 106.

- Good visibility.

- Restyled Rover Metro. CVT auto was one of the best.

- Rovers generally had slightly below average warranty repair costs in 2003 Warranty Direct Reliability index (index 93.69 v/s lowest 31.93), just beating Nissan. Link:- www.reliabilityindex.co.uk

Bad

- Cramped cabin due to bigger, more luxurious seats in same size body as original Metro.

- Heavy, non-power-assisted steering - the wider the tyres the heavier it is.

- Diesel very slow and not that economical if worked hard.

Watch

- Oil leaks from engine.

- Cracked cylinder heads (look for mayo under oil cap). Head gasket leaks due to stretched or re-used stretch bolts which go all the way to the sump.

- Tappety noises.

- Abused 16-valve versions.

- Kerbed alloy wheels (suspect suspension damage). Many went to driving schools.

- Some were built long before they were UK registered.

- Rear wheel studs come loose from hubs.

- If twin-cam 16v K-Series suffers cabin boom at idle the engine mount is worn at the timing belt end(not enough rubber). Replacement mounts £48 + VAT. Check rear wheel arches for rust or bodge.

- First places to look for rust and filler are the gutter seams and rear wheel arches.

- K-Series engine inlet manifold 'O' rings tend to perish between 25 - 30,000 miles.

- Head gasket failure common because very low coolant capacity of engine means small leaks rapidly lead to overheating. Weakest point is water heated inlet manifold gasket.

- Rear wheel arches highly prone to corrosion.

- Central locking solenoids fail regularly.

- Radiator matrix apt to get blocked with mud and flies, then the fins disintegrate. Not good on engines highly sensitive to cooling system problems.

- Misfires on K-Series commonly caused by failed resistor in rotor arm or by water ingress to coil as well as faulty ECU.

- Check CVT carefully for clunks selecting drive (failing electromagnetic clutch) and jerky running when on the move (failing CVT bands). Needs fresh transmission fluid every 2 years and must always be kept up to the level.

- K-Series engine inlet manifold 'O' rings tend to perish between 25 - 30,000 miles.

- Head gasket failure common because very low coolant capacity of engine means small leaks rapidly lead to overheating. Weakest point is water heated inlet manifold gasket.

- Rear wheel arches highly prone to corrosion.

- Central locking solenoids fail regularly.

- Radiator matrix apt to get blocked with mud and flies, then the fins disintegrate. Not good on engines highly sensitive to cooling system problems.

- Misfires on K-Series commonly caused by failed resistor in rotor arm or by water ingress to coil as well as faulty ECU.

AROnline buying guide

Engine and transmission:

The K-Series engine is generally reliable, but does have a tendancy to leak oil. Head gaskets are known to be weak, and will eventually go even on a well maitained car. If this is not rectified immediatly many cars will just go on, but many will need a new head later. It is in any case expensive not to repair this immediatly, as the coolant hoses will need replacement when in contact with oil for too long. However, if the car has been treated properly (regular serviceing, correct coolant strength, allowing engine to warm up before hard revving,) they should be OK. (check for oil in coolant and water in oil). GTa and GTi models are very likely to have been through a hard life, so a service history is essential on these models. Make sure the cambelt has been changed at 60,000 miles.

There are no major issues with the Peugeot sourced TU engine.

The R84/R85 manual boxes are generally fine in the Metro application, however they can make some noise from the input shaft bearing, and can crunch into reverse. This is nominal, and shouldn’t give cause for concern. It is also worth noting that it can cause problems on the higher powered cars; there have been cases of broken gears. Early gearboxes can leak oil through the breather (which could be replaced with the later breather).

Suspension, steering and brakes:

The Moulton Hydragas setup on the R6 is a joy, and really does give a big-car feel to a small car, however watch for the car being down on one side (particularly at the front) as this could indicate a worn hydragas displacer, however it could just need a pump-up.

Check the rear radius arms for play (an MoT failure) – if these have not been properly maintained, you will be able to easil spot an offending car by its negative camber angle on the rear wheels. In many cases then the rear arms are not saveable by this time and will need expensive replacement.

This is also the same for the front top arm: these have grease nipples and are frequently forgotten.

The steering is generally very direct, with no power assistance. Main things to check for are worn gaiters.

Brakes are generally OK, however the handbrake is manually adjusted and the adjusters have a tendancy to stick. Some WD-40 and a quality brake adjusting spanner should free this off.

Body and chassis:

The main enemy of any Metro/100 is rust. Rear wheel arches, floorpans and outer sills are known to be weak spots. Get the car on ramps and check the floor/sills for bodged repairs. Rear repair panels are commonly available (and cheap), so there is NO excuse for bodging here.

Interior:

Generally very hard-wearing but more visible on lighter coloured interiors.

Electrical system:

Generally reliable. A nice simple system produces few problems. however on later Metros (’93-95), ensure that if there is no remote keyfob, the alarm/immobiliser has been disabled, as the immobilser ECU is under the facia, and the facia will reqiure removal to access this.

On Rover 100s ensure the 4-digit immobiliser code is supplied (about £10 from a dealer) to allow the alarm to be de-activated should the remote keyfob fail.

On the 16v versions the alternator suffers the heat build-up from the exhaust manifolds and will eventually pack up – look out for the heat shield of the alternator. Engine ECU’s are known to stop working at about 10 years. Central locking and electric windows can give additional trouble.

.jpg?width=640&height=426&rmode=crop)

.jpg?width=640&height=426&rmode=crop)

.jpg?width=640&height=426&rmode=crop)

.jpg?width=640&height=426&rmode=crop)

.jpg?width=640&height=426&rmode=crop)